About Me

Journalists have bestowed on me the tag of “world’s most influential living philosopher.” They are probably thinking of my work on the ethics of our treatment of animals, often credited with starting the modern animal rights movement, and of the influence that my writing has had on the development of effective altruism. I am also known for my controversial critique of the sanctity of life ethics in bioethics.

In 2021, I was delighted to receive the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy and Culture. The citation referred to my “widely influential and intellectually rigorous work in reinvigorating utilitarianism as part of academic philosophy and as a force for change in the world." The prize comes with $1 million, which, in accordance with views I have been defending for many years, I have donated to the most effective organizations working to assist people in extreme poverty and to reduce the suffering of animals in factory farms.

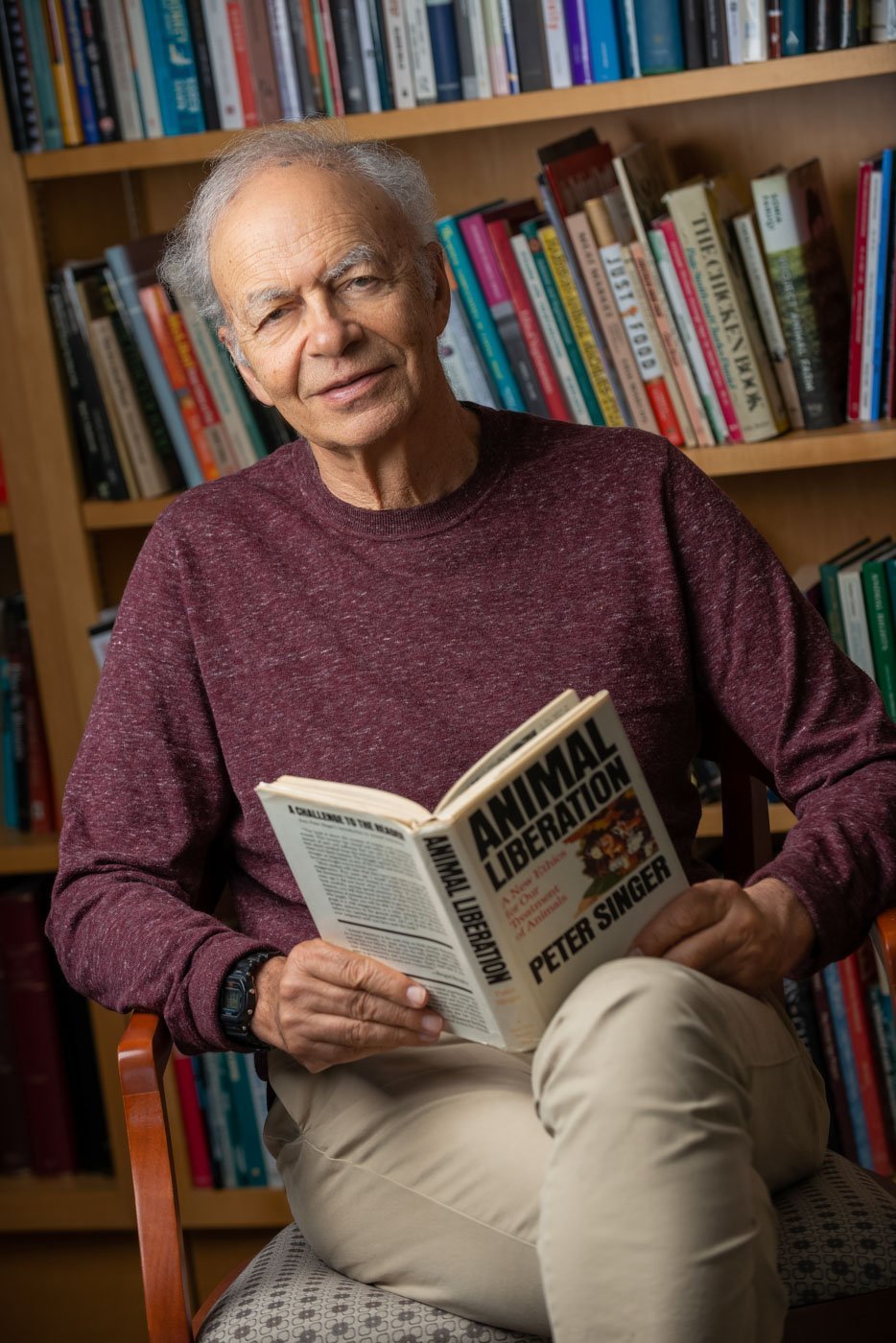

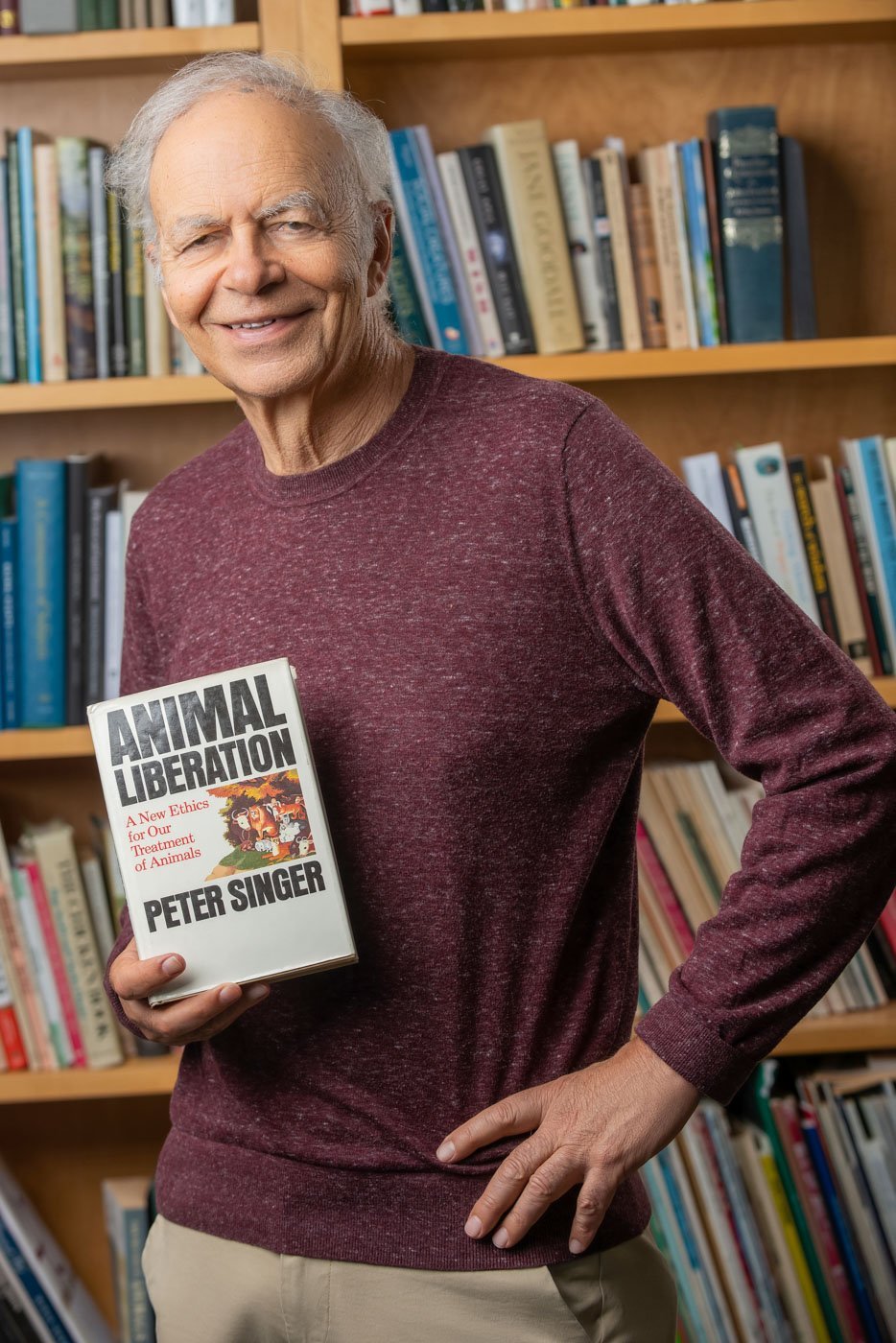

My wife, Renata, and I stopped eating meat in 1971 because we recognized that there is no ethical justification for treating animals as if their interests didn’t count. That realization led me to write Animal Liberation, first published in 1975. Several key figures in the animal movement have said that this book led them to get involved in the struggle to reduce the vast amount of suffering we inflict on animals. To that end, I co-founded the Australian Federation of Animal Societies, now Animals Australia, the country's largest and most effective animal organization.

I am the founder of The Life You Can Save, an organization based on my book of the same name. It aims to spread my ideas about why we should be doing much more to improve the lives of people living in extreme poverty and how we can best do this. You can view my TED talk on this topic here.

My writings in this area include the 1972 essay “Famine, Affluence, and Morality”, in which I argue for donating to help the global poor, and two books that make the case for effective giving, The Life You Can Save (2009, 2nd edition 2019) and The Most Good You Can Do (2015).

I have written, co-authored, edited or co-edited more than 50 books, including Practical Ethics, The Expanding Circle, Rethinking Life and Death, One World, The Ethics of What We Eat (with Jim Mason) and The Point of View of the Universe (with Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek). My writings have appeared in more than 30 languages.

I was born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1946 and educated at the University of Melbourne and the University of Oxford. I have taught in England, the United States, and Australia. For 25 years I was the Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University. I now spend my time working on my podcast, my Substack and doing research and writing in Melbourne, so that Renata and I can spend time with our three daughters and four grandchildren. We also enjoy hiking, and I surf.

THE ETHICS OF OUR TREATMENT OF ANIMALS

-

In 1970, when I was a graduate student at Oxford, a chance lunch with Richard Keshen, a Canadian graduate student and a vegetarian, introduced me to concerns about factory farming. This led me to deeper study and awareness about the way we treat non-human animals. Eventually I wrote Animal Liberation, which has been described as the “bible” of the animal rights movement. It was published in 1975 and has never been out of print.

I’ve been active in the animal movement in England, Australia and the US. I co-founded the Australian Federation of Animal Societies, which is now Animals Australia, the largest campaigning organization for animals in that country. I also worked with Henry Spira in the United States, and wrote about his remarkable work in Ethics into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights Movement. Together with Jim Mason, I wrote The Ethics of What We Eat.

I’ve been a vegetarian since 1971, and now describe myself as a flexible vegan, meaning that I am mostly vegan, but not fanatical about avoiding all animal products when it is difficult to do so. The point is, in my view, to minimize support for industries that are causing billions of animals to lead miserable lives, or to die in painful ways. It's been very encouraging to see the spread of vegan foods and restaurants in so many countries over the past decade.

I support organizations trying to reduce the suffering of animals, especially animals raised or killed for food, because the numbers involved in the use of animals for food dwarfs every other abuse of animals. If you’d like to help animals with your charitable giving, I suggest you consider the recommendations of Animal Charity Evaluators.

BIOETHICS

-

I’ve always been interested in ethical questions that have some application to the world. As I was starting my career in philosophy, we began seeing the rapid introduction of new discoveries in medicine and the biological sciences. Early discussions of the ethics of these new techniques — for example, in vitro fertilization — were dominated by bishops and theologians. Sometimes they would debate scientists, who can provide facts but don’t necessarily have expertise in ethics. That’s where I felt philosophy can play an essential role. We need to have ethical discussions about such questions as end-of-life decisions in health care, the use of embryos in research, and genetic selection or modification of our offspring. I teach about some of these issues in my courses at Princeton University, and I have written about them in books like Rethinking Life and Death, Practical Ethics and Ethics in the Real World: 82 Brief Essays on Things That Matter.

EFFECTIVE ALTRUISM

-

Effective altruism is built on the simple but unsettling idea that living a fully ethical life involves doing the most good one can. Often, the most practical way of doing this is giving to effective organizations, but effective altruism can also affect the choice of career and the voluntary work you do.

Doing the most good you can may mean reducing the suffering of other people, or of animals, or reducing the risks of future catastrophes. My focus has been on improving the lives of people in extreme poverty. In my 1972 article “Famine, Affluence and Morality,” (now a short book) I asked readers to imagine that they were walking by a pond in which a small child was drowning. They would, I suggested, be likely to rush in to save the child, even if it meant ruining an expensive pair of shoes they were wearing. This “Child in the pond” thought experiment prompts people to think about their values and actions. If most of us would not think twice about the cost of buying new shoes compared to saving a life, why do so few people donate to organizations that are proven to dramatically improve or save the lives of those in extreme poverty, often at a modest cost?

I developed my argument for this thinking most fully in my books The Life You Can Save and The Most Good You Can Do, and I co-founded the nonprofit organization The Life You Can Save in order to promote effective giving to help people in extreme poverty.

If you’d like to learn more about effective altruism, I teach a free online course on this topic and discuss it at length in many of the writings and videos referenced here, particularly in my book The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically.

Credit: Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek, katarzyna.delazari@uni.lodz.pl

Credit: Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek,katarzyna.delazari@uni.lodz.pl

Credit: Alana Holmberg, hi@alanaholmberg.com

Credit: Alana Holmberg, hi@alanaholmberg.com

Credit: Alana Holmberg, hi@alanaholmberg.com

Credit: Alana Holmberg, hi@alanaholmberg.com

Credit: Alana Holmberg, hi@alanaholmberg.com

Credit: Alletta Vaandering

Credit: Tony Phillips

Credit: Alletta Vaandering

Credit: Seth Lazar

Credit: Denise Applewhite

Credit: Derek Goodwin, pashupa@derekpashupagoodwin.com.

Credit: Derek Goodwin, pashupa@derekpashupagoodwin.com.

Credit: Derek Goodwin, pashupa@derekpashupagoodwin.com

Credit: Derek Goodwin, pashupa@derekpashupagoodwin.com.

Credit: Derek Goodwin, pashupa@derekpashupagoodwin.com

For photos by Alletta Vaandering or for high-resolution images suitable for reproduction, please contact her at http://www.allettavaandering.com/contact/For photos by Derek Goodwin: These images are copyrighted, and may not be copied or reproduced without the permission of the photographer. He will supply high-resolution images suitable for reproduction and will not charge fees to non-profit organizations. His email is: dgoodwin@mac.com.FAQs

-

We should give where it will do the most good. There is no sound moral reason for favoring those who happen to live within the borders of our own country. Sometimes, just because they are closer to us and living within the same political system, they may be the people we can most effectively help. More often they will not be. If we live in a rich nation like the U.S.A., our money will go much further, and help more people, if we send it to an organization working in developing nations. About a tenth of the world’s population survives on the purchasing power equivalent of less than US$2 per day. For a more detailed statement of my views on this topic, see The Life You Can Save.

-

I’m not living as luxurious a life as I could afford to, but I admit that I indulge my own desires more than I should. My wife and I give about a third of what we earn, both to organizations helping the poor to live a better life and to reducing animal suffering. I don’t claim that this is as much as I should give. Since we started giving, about forty-five years ago, we’ve gradually increased the amount we give. Giving half is the next target. At the nonprofit I founded, The Life You Can Save, we call this strategy of improving one’s giving behavior, "Personal Best."

-

You can see an indication of the anti-poverty organizations I support from the website of The Life You Can Save and its list of recommended charities. Another influence on my giving is research of the charity evaluator GiveWell.

When it comes to reducing the suffering of animals, I am influenced by the recommendations of Animal Charity Evaluators.

-

It’s not so clear that the problem really is too many people, rather than that some people have a lot more than they need, and others not enough. But that’s a large question that I am currently interested in investigating more deeply. I do agree that continued global population growth is likely to make the world’s problems more difficult to solve. One proven way of reducing fertility is enabling poor people, especially women, to get some education. Women with even just a year or two of primary school education have fewer children than women with no education. So development aid does slow fertility. But if you want to do something more directly related to population issues, you could give to organizations like Population Services International, or DKT International.

-

I argued in the opening chapter of Animal Liberation that humans and animals are equal in the sense that the fact that a being is human does not mean that we should give the interests of that being preference over the similar interests of other beings. That would be speciesism, and wrong for the same reasons that racism and sexism are wrong. Pain is equally bad, if it is felt by a human being or a mouse. We should treat beings as individuals, rather than as members of a species. But that doesn’t mean that all individuals are equally valuable – see my answer to the next question for more details.

-

Yes, in almost all cases I would save the human being. But not because the human being is human, that is, a member of the species Homo sapiens. Species membership alone isn't morally significant, but equal consideration for similar interests allows different consideration for different interests. The qualities that are ethically significant are, firstly, a capacity to experience something — that is, a capacity to feel pain, or to have any kind of feelings. That's really basic, and it’s something that a mouse shares with us. But when it comes to a question of taking life, or allowing life to end, it matters whether a being is the kind of being who can see that he or she actually has a life — that is, can see that he or she is the same being who exists now, who existed in the past, and who will exist in the future. Such a being has more to lose than a being incapable of understanding this. Any normal human being past infancy will have such a sense of existing over time. I’m not sure that mice do, and if they do, their time frame is probably much more limited. So normally, the death of a human being is a far greater loss to the human than the death of a mouse is to the mouse — for the human, it thwarts plans for the distant future, and it does not do that for the mouse. And we can add to that the greater extent of grief and distress that, in most cases, the family of the human being will experience, as compared with the family of the mouse (although we should not forget that animals, especially mammals and birds, can have close ties to their offspring and mates). That’s why, in general, it would be right to save the human, and not the mouse, from the burning building, if one could not save both. But this depends on the qualities and characteristics that the human being has. If, for example, the human being had suffered brain damage so severe as to be in an irreversible state of unconsciousness, then it might not be better to save the human.

-

I was asked about such an experiment in a discussion with Professor Tipu Aziz, of Oxford University, as part of a BBC documentary called “Monkeys, Rats and Me: Animal Testing" that was screened in November 2006. I replied that I was not sufficiently expert in the area to judge if the facts were as Professor Aziz claimed, but assuming they were, this experiment could be justified.

This response caused surprise among some people in the animal movement, but that must be because they had not read what I have written earlier. Since I judge actions by their consequences, I have never said that no experiment on an animal can ever be justified. I do insist, however, that the interests of animals count among those consequences, and that we cannot justify giving less weight to the interests of nonhuman animals than we give to the similar interests of human beings.

In Animal Liberation I propose asking experimenters who use animals if they would be prepared to carry out their experiments on human beings at a similar mental level — say, those born with irreversible brain damage. Experimenters who consider their work justified because of the benefits it brings should declare whether they consider such experiments justifiable. If they do not, they should be asked to explain why they think that benefits to a large number of human beings can outweigh harming animals, but cannot outweigh inflicting similar harm on humans. In my view, this belief is evidence of speciesism.

Even if some individual experiments may be justified, this does not mean that the institutional practice of experimenting on animals is justified. Given the suffering that this routinely inflicts on millions of animals, and the likelihood that very few of the experiments will be of significant benefit to humans or to other animals, it is better to put our resources into other methods of doing research that do not involve harming animals.

Incidentally, it is important that there be room in the animal movement for a variety of views about ethics, including views that are rights-based and views that are consequentialist. Debate over such issues is a sign of an open and sound movement. On the other hand, it is also important to focus our energies on attacking speciesism, and not those who, although opposed to speciesism, do not share the particular set of moral views we may hold.

-

Yes, growing meat at the cellular level would be ethically acceptable, because no animals would suffer or die to produce it. There's nothing wrong with meat in itself.

If people prefer the taste of meat grown from the cell of a cow to meat grown from the cell of a human, that's fine too. So there's no ethical requirement to grow human meat for consumption, just because we're growing meat from other animals.

-

I did write that, in the 1979 edition of Practical Ethics. Today the term “defective infant” is considered offensive, and I no longer use it, but it was standard usage then. The quote is misleading if read without an understanding of what I mean by the term “person” (which is discussed in Practical Ethics). I use the term "person" to refer to a being who is capable of anticipating the future, of having wants and desires for the future. As I have said in answer to the previous question, I think that it is generally a greater wrong to kill such a being than it is to kill a being that has no sense of existing over time. Newborn human babies have no sense of their own existence over time. So killing a newborn baby is never equivalent to killing a person, that is, a being who wants to go on living. That doesn’t mean that it is not almost always a terrible thing to do. It is, but that is because most infants are loved and cherished by their parents, and to kill an infant is usually to do a great wrong to her or his parents.

Sometimes, perhaps because the baby has a serious disability, parents think it better that their newborn infant should die. Many doctors will accept their wishes, to the extent of not giving the baby life-supporting medical treatment. That will often ensure that the baby dies. My view is different from this, but only to the extent that if a decision is taken, by the parents and doctors, that it is better that a baby should die, I believe it should be possible to carry out that decision, not only by withholding or withdrawing life-support — which can lead to the baby dying slowly from dehydration or from an infection — but also by taking active steps to end the baby’s life swiftly and humanely.

-

Most parents, fortunately, love their children and would be horrified by the idea of killing it. And that’s a good thing, of course. We want to encourage parents to care for their children, and help them to do so. Moreover, although no newborn baby has a sense of the future, and therefore no newborn baby is a person, that does not mean that it is all right to kill any newborn baby. It only means that the wrong done to the infant is not as great as the wrong that would be done to a person who was killed. But in our society there are many couples who would be very happy to love and care for an infant without serious disabilities. Hence even if the parents do not want their own child, it would be wrong to kill it. Although there are also sometimes couples willing to adopt, love and care for infants with serious disabilities, that is not always the case.

-

When a human being once had a sense of the future, but has now lost it, we should be guided by what he or she would have wanted to happen in these circumstances. So if someone would not have wanted to be kept alive after losing their awareness of their future, we may be justified in ending their life; but if they would not have wanted to be killed under these circumstances, that is an important reason why we should not do so.

-

I support law reform to allow people to decide to end their lives, if they are terminally or incurably ill. This is permitted in the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Colombia, and in the form of physician-assisted dying, in Canada, too, as well as in several states of the US, including Oregon, Washington, California, Montana, Colorado and Vermont. I was very pleased when, in 2017, after extensive debate in the community and in parliament, physician assistance in dying was legalized in Victoria, where I am from. Why should we not be able to decide for ourselves, in consultation with doctors, when our quality of life has fallen to the point where we would prefer not to go on living?

-

You might like to start with one of the two collections of my work in print, Writings on an Ethical Life, or Unsanctifying Human Life. After that, your choice should depend on what particular issues most interest you. For my views about animals, see Animal Liberation. The fullest statement of my critique of the traditional doctrine of the sanctity of human life is in Rethinking Life and Death, and the most elaborated philosophical elaboration of my views is Practical Ethics, now in its 3rd edition (2011). My more recent books are described elsewhere on this website.

These books are in many libraries. They can also be ordered from bookstores, or from online retailers like Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

My views are not fixed. Many good philosophers disagree with me, and all philosophers should be open to changing their views on the basis of new arguments and objections. I am currently reconsidering some of the answers given above, especially those in which I regard the wrongness of killing as significantly affected by the capacity of those killed to see themselves as existing over time. This is a view that derived from my earlier acceptance of preference utilitarianism, but it does not fit well with hedonistic utilitarianism, which I am now more inclined to favour. (See Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer, The Point of View of the Universe)

CONTACT

CONTACT

I value every email I receive, but due to the overwhelming volume I can only respond to a few. If unanswered, please refer to the FAQs above and accept my apologies for the constraints of time.